On 18 June 2025, the European Council and the European Parliament reached a provisional agreement on the Omnibus-I legislative package: which seeks to simplify the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). Omnibus-I aims to reduce the compliance burden on European importers, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and simplify CBAM mechanism for them. However, despite these internal simplifications, significant challenges persist for Indian exporters and other third-country suppliers navigating the EU’s evolving carbon regulation landscape. Further, Omnibus-I does not address the underlying issues at the heart of CBAM reporting, which begs the question whether the European Commission is even aware of the evolving ground realities. We first discuss Omnibus-I and then highlight certain key issues that need to be addressed before the definitive phase of CBAM begins.

What is CBAM?

CBAM is a central component of the European Union’s ‘Fit for 55’ package, which aims at reducing greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030, relative to 1990 levels. CBAM places a carbon price on the embedded emissions in imported goods of six carbon-intensive sectors namely cement, aluminium, iron and steel, hydrogen, electricity, and fertilisers (CBAM goods).

The EU claims that CBAM has been designed to put a fair price on the carbon emitted while manufacturing the goods being imported into the EU and prevent carbon leakage, a phenomenon where businesses start relocating industries to or import products from countries, with less stringent environment policies, apparently to circumvent the cost-intensive climate policies in the EU.

How is CBAM being implemented?

CBAM is being implemented in two distinct phases:

1. Transitional phase (October 2023 – December 2025):

During this phase, the EU importers are required to declare the embedded emissions of imported CBAM goods. However, they are not yet required to purchase and furnish CBAM certificates based on these emissions meaning thereby, there is no financial liability as such during the transitional phase. This phase aims businesses familiarising themselves with the nuances of CBAM, coordinate with internal and external stakeholders to collect the relevant data, and adapt to the reporting requirements. At the same time the European Commission could use this phase to collect country-wise emissions data, identify potential issues, and make necessary changes and adjustments to the CBAM regulation.

2. Definitive Phase (Starting January 2026)

From 2026, the EU importers would be required to purchase and furnish CBAM certificates to a certain threshold in advance. The liability shall be finalised in 2027 after the CBAM reports are verified. This would effectively put a carbon cost on the imported CBAM goods.

Although the transitional phase does not involve financial obligations, it has already begun to influence trade flows which highlights its practical impact.

Impact of CBAM on imports into the EU and Indian exports

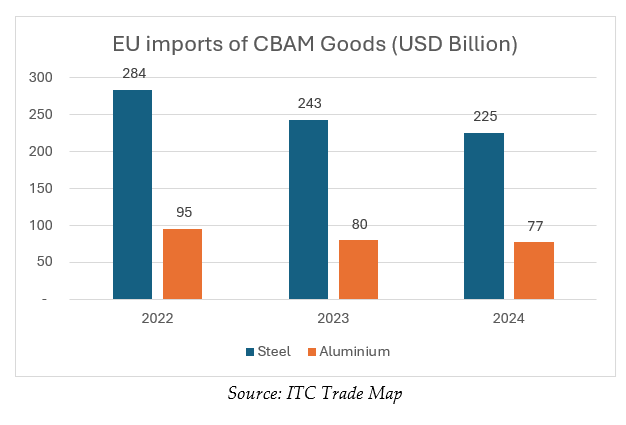

Over the course of the ongoing transitional phase, six quarterly reports have been submitted by European importers to the European Commission. Trade data reveals that even without any financial implication, there has been a significant decline in the import of CBAM goods into the EU. Specifically, in comparison to 2022, in 2024 –

• steel and steel products imports have declined by 21%

• aluminium imports have dropped by 19%

This downward trend is expected to intensify as CBAM enters its definitive phase in 2026 and European importers are required to purchase and surrender CBAM certificates based on the embedded emissions of their imports. This drop can be attributable to certain other factors as well such as decline in demand and trade protection measures by the EU such as safeguard duties on imports of steel. The trend of EU imports of CBAM goods under the iron and steel (in HSN chapters 72 and 73) and aluminium (in HSN Chapter 76) sectors is as below:

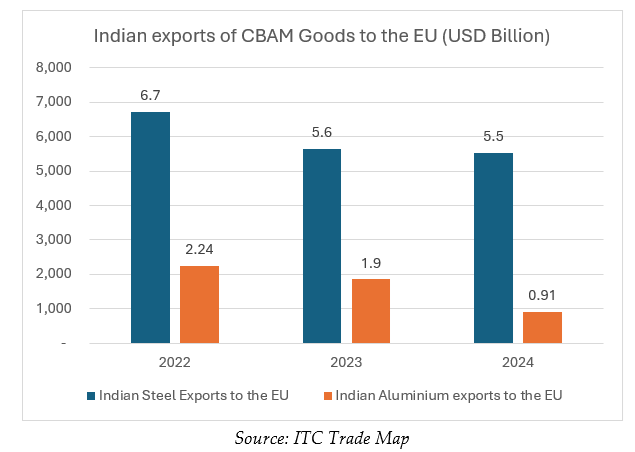

A deeper analysis of the import data shows that there has been a significant reduction in the imports of primary iron and steel goods, like bars, rods, angles, etc. A similar declining trend can be observed in the exports of CBAM goods from India to the EU as well.

In addition to decline in exports of primary iron and steel products, the exports of Indian aluminium products have also declined significantly. In comparison to 2022, in 2024, while the Indian exports of steel products decreased by 18%, the aluminium exports had a steeper fall of 59%. These trends highlight that even in the absence of any financial implication under the CBAM, the compliance obligations under CBAM transitional phase may have contributed to altering trade dynamics. The imports might plummet further once the definitive phase comes into effect in 2026 as the complexities of compliance will then be accompanied by the financial implication of purchasing CBAM certificates by the EU importers. Such decisions must rely on accurate CBAM data, for which the EU importers depend on their overseas suppliers where the actual manufacturing of CBAM goods occurs.

Why is the EU simplifying CBAM?

In light of the growing concerns about complexity and administrative burden, especially for SMEs, the European Commission has proposed a set of simplification measures to smoothen the implementation process.

Key highlights of the Omnibus-I simplifications:

1. Quantum based exemption threshold introduced: Currently, import consignments of a value below EUR 150 are exempted from compliance requirements of the CBAM. Omnibus-I revises the exemption threshold to a cumulative quantum-based threshold of 50 tonnes of imports of CBAM goods per importer per calendar year. According to the EU, this shift will exempt nearly 90% of importers while still covering 99% of emissions under the mechanism. This threshold applies to sectors other than hydrogen and electricity.

An important caveat for third-country manufacturers is that this proposed exemption applies to importers within the EU, and not manufacturers in third countries such as India. This means that even if a manufacturer is exporting less than 50 tonnes to the EU but its EU customer is cumulatively importing more than 50 tonnes, then even such manufacturers will be required to continue monitoring and reporting their CBAM data to their EU customer.

2. Verification requirements limited to actual values only: Omnibus-I states that the verification of embedded emissions by accredited verifiers must be done for the actual emission values only, as the default values are being prescribed by the EU after careful examination and analysis. To further simplify the process, it has been proposed that the accredited verifiers should have access to the CBAM Registry, from where the emission values can be verified directly, after obtaining permissions from the manufacturers in non-EU countries.

However, since July 2024 onwards, the permitted share of default values was capped at 20% , which would limit the impact of this simplification. Therefore, even though the verification has been proposed to be limited to actual values, 80% of the emissions remain subject to verification.

3. Carbon price paid in third countries taken into account: The CBAM Regulation takes into account the carbon price paid in the ‘country of origin’. Omnibus-I modifies this to carbon price paid in ‘a third country’, thereby providing increased flexibility in adjusting the carbon price already paid in third countries and removing the burden to identify country of origin. The simplification further proposes to introduce default carbon prices that may be used in cases where the effectively paid carbon price cannot be determined. This modification will allow adjustment of the carbon price already paid in a third country without having the burden to prove that it is the country of origin.

4. Reduced Financial Obligation for management of CBAM Certificates: As per the existing CBAM Regulation, a CBAM declarant in the EU must ensure that the number of CBAM certificates available on its account in the CBAM Registry correspond to at least 80% of the embedded emissions at the end of each quarter. Omnibus-I proposes to reduce this to 50%. This proposed modification reduces the financial burden on EU importers and allows them to free up capital that would otherwise remain locked in.

5. Exclusion of Input Materials procured from the EU: If the raw materials (precursors) have already been subject to the EU Emission Trading System (‘ETS’), their embedded emissions will not be accounted for in the calculation of the downstream goods being manufactured. This will eliminate double counting of the same emissions and simplify CBAM reporting.

6. Extended deadlines for CBAM Declarations: Under the current deadlines, the CBAM declarants shall be required to submit their CBAM declaration and surrender CBAM certificates for 2026 emissions by 31 May 2027. Omnibus-I extends this date to 30 September 2027.

7. Exclusion of certain low emissions: Omnibus-I proposes to exclude certain iron and steel, and aluminium goods, where emissions primarily result from embedded emissions of input materials.

What the Omnibus misses

While the simplification proposals are welcome, and there is of course, more room for improvement, there are some crucial elements that the Omnibus misses. At the heart of the CBAM quarterly reporting during the transitional phase is the underlying embedded emissions data of CBAM goods. The embedded emissions data pertain to direct and indirect emissions of the overseas manufacturer.

Direct emissions pertain to emissions that relate to the production process of a product, while indirect emissions pertain to the electricity used in such production. During the initial years of CBAM, the EU shall be collecting CBAM prices only against the direct emissions component and not the indirect emissions. This calls for the need to know in advance what the financial liability would be beginning 2026 so that the EU importers can plan their procurements from those overseas suppliers whose products will potentially lower the financial liability of the EU importers.

As a result, there has been a race to declare the lowest possible embedded emissions, and sometimes, at all costs. To complicate things further, the CBAM regulation mandates that starting July 2024, 80% of the embedded emissions must be based on actual data and only 20% of the declared emissions can be based on notional or assumed values which the CBAM regulation terms as “default values”. The EU has already put in public domain such default values for all CBAM goods. It is no surprise that these default values are very high, leading to declaration of high embedded emissions, which means potentially high CBAM financial liabilities for EU importers.

So, then, what has the market response been? Use actual data, or at least pretend to use one, and get it certified by a verifier. It is to be noted that verification is not mandatory during the transitional phase and the EU has not yet published a list of accredited verifiers. But under pressure from their EU customers or in their interest to look good and protect the important EU market, overseas manufacturers are getting their embedded emissions verified. What is at stake is trust and confidence in the reporting system which has sort of got muddied. Consider the following scenarios to understand what is happening on the ground:

i. Embedded emissions of a product include embedded emissions of the raw materials used in that product as well. Only those raw materials that are themselves CBAM goods need to be included. The overseas manufacturers must properly account for the consumption of such raw materials. The issue is, raw material consumption may not be properly recorded in the books, and thus, notional raw material consumption needs to be used. While this approach may still be acceptable to an extent, the problem arises when different consumption norms are used every quarter without valid justification.

ii. To further complicate things, the manufacturer is unable to trace from whom they purchased the raw material which was consumed in production. Raw material inventories get mixed and are fungible, leading to loss of traceability. But CBAM reporting requires the use of actual embedded emissions values of raw material suppliers. If you cannot ascertain who the raw material supplier is, use default values then, which would lead to higher embedded emissions of your finished product.

Since July 2024, due to the legal requirement to have CBAM values based on 80% actual data, things have become complex. Manufacturers are validly worried that if they are unable to demonstrate compliance with this requirement, they will lose orders from their EU customers. Traceability of the embedded emissions to the actual source is most important and this is getting overlooked.

iii. Even raw material suppliers may not have attempted calculations of their CBAM embedded emissions, and they are not interested in this exercise too. Their reasons could be that the EU is not their market or their exports to the EU are not much and therefore, they are not interested in such compliance burden for their Indian customers who manufacture finished products using their raw material. The only option left is to use default values for such raw material suppliers or replace this raw material supplier’s default values with actual values of a different raw material supplier. The logic seems to be that as both raw material suppliers supply the same input, one raw material supplier’s actual embedded emissions can be used for another one. But is this legally correct?

iv. It thus makes sense that the adoption of tech platforms for CBAM monitoring and reporting is taking time. These platforms may connect overseas manufacturers with their EU customers and bring in more transparency. For that, the overseas manufacturers must first gain confidence that they are ready to report CBAM data transparently to their EU customers while ensuring that the confidentiality of data is maintained.

v. This is the state of the data that is getting ‘verified’. And these are just a few issues.

The EU places a lot of importance on CBAM as the key in –

- preventing carbon leakage,

- onboarding foreign manufacturers to join in climate change mitigation and reduce their emissions to access the EU market, and

- CBAM goods attracting a fair CBAM price.

The question is that for the CBAM price to be fair, it is the quality of the underlying embedded emissions data that matters and the ethics of reporting it. Otherwise, it could lead to a situation where only the EU’s own domestic industry pays a fair carbon price and not the rest. This will be a failure of the CBAM project and a disservice to the planet.

The EU importers are placing a lot of trust on their overseas manufacturers and planning their potential financial exposure in advance. They could be in for a surprise when they face the final CBAM bill in 2027. Therefore, the underlying issues in CBAM reporting must be thought through and addressed before they get carried over to the definitive phase and then, it will be too late.

The way forward

Now, the European Council and the European Parliament must endorse the provisional simplification proposal for formal adoption. This is expected to happen by September 2025. As the definitive phase of the CBAM nears, other information, including publication of revised default values, criteria for accredited verifiers etc., are also awaited. At this juncture, it is important for the EU importers and manufacturers in other countries alike to continue compliance with the CBAM in a robust and ethical manner, and work on improving their monitoring, and data collection methodologies to provide accurate embedded emission data.

[The authors are Partner, Principal Associate and Associate, respectively, in International Trade and WTO practice at Lakshmikumaran & Sridharan Attorneys, New Delhi]